Scarlet Fever and other Memories.

Logan has spots. They can't be chicken pox. He's had that. Neither can they be measles. He's been vaccinated. I suggested the only other thing was Scarlet Fever. The doctor said it's likely a strain of the streptococcus bacteria. His mother looked it up and discovered when strep erupts through your skin, that’s Scarlet Fever.

Years ago, Scarlet Fever was classified as a Childhood Infectious Disease. The patient was carried off in a red blanket to Isolation Hospital. Brothers and sisters had to stay off school and the house had to be fumigated. A bucket would be placed in the centre of a room. Something was activated and the doors sealed with sticky tape. We had to stay out for a matter of hours.

Whether or not it was effective, I have no idea.

Houses were two rooms usually but some were one. Entire families would sleep in a couple of beds. My father and brother slept in one. My mother, two sisters and myself in the other. The beds were called set-in beds. They were like cupboards in the wall with curtains that could be closed across the front. The platform would be high enough to store stuff underneath. Like the wicker basket full of laundry and a wooden rocking horse with hair that came from my paternal grandmother's house. We never got to play with it. Most of the living was done in the kitchen. The coal range was there. Also the sink, with a cold water spigot. Light was a gas mantle above the fire. There was a communal wash-house in a corner of the yard, with a row of four coal cellars on either side. Backing on to the wash-house and therefore behind the wall formed by the coal cellars was the communal lavatory. It was so old, the stone slab where feet rest ed was worn to a hollow. I never remember it being anything but clean. There were eight families with numerous children using that lavatory. The door was held shut by a big rock. The top and bottom edges of the door looked like they had been gnawed at. What had originally been a knothole in the centre had grown to nine inches long and four wide. You might say it was weather-beaten.

Most of the living was done in the kitchen. The coal range was there. Also the sink, with a cold water spigot. Light was a gas mantle above the fire. There was a communal wash-house in a corner of the yard, with a row of four coal cellars on either side. Backing on to the wash-house and therefore behind the wall formed by the coal cellars was the communal lavatory. It was so old, the stone slab where feet rest ed was worn to a hollow. I never remember it being anything but clean. There were eight families with numerous children using that lavatory. The door was held shut by a big rock. The top and bottom edges of the door looked like they had been gnawed at. What had originally been a knothole in the centre had grown to nine inches long and four wide. You might say it was weather-beaten.

Families took turns scrubbing and cleaning. There were never any arguments about it.

There was a drying green at the end of the yard. Between it, and the wall formed by the coal cellars, each tenant had a patch of garden. They grew their own vegetables and most had a rhubarb patch.

Wee Donald McNab had a "midden" - a compost pile. Donald grew sweet peas in his garden as well as vegetables. He worked at the shipyard. He had a trade. He and wife Maggie had four children - Allan, Margaret, Willie and wee Donald. They had Sunday clothes, books to read, and they got comics every week.

Mrs. McNab, always had sweeties. Her children would get one most evenings.Sometimes she would share. She also had a penny bank. It was a bust of a black man and sat on the mantlepiece. The jacket was red and the tongue came out to receive the penny.

The gas meter took pennies. If you ran out of gas and pennies, you had no light . We went to bed and told stories when that happened. There were often disputes about the pennies and why they needed to be there.

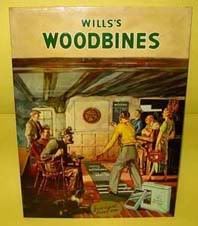

My father smoked Will's Woodbine cigarettes. They came in little paper packets of five. They were cheap. He also rolled his own "fags". The old men smoked pipes. Some old women smoked little white clay pipes. That was considered pretty low class.

Wee Donald's mother lived close by. Everyone knew her as Auld Granny McNab. She wore skirts to the ground, a black shawl over her shoulders and her hair in a bun. She wandered about talking to herself and searching for her "Babby". She picked up little bits of stick wherever she found them and frequently came banging on Wee Donald's door in the middle of the night, crying for her lost "Babby”. It seems a baby had died and she had lost her mind. Whether at the same time I do not know. Granny was a sad, forlorn and familiar creature in the world of my childhood.

Like the rest of the men, Wee Donald got drunk on Saturday night. Maggie had to wait up for him. His habit was to lie on the floor and kick everything within reach. So, Maggie stayed up to remove his boots. Then the only thing he could hurt were his feet and that helped to stop the kicking.

The door into their house was less than three feet directly across from ours. In the evening, quite often, Mrs McNab and my mother would stand in their respective doorways, arms folded, leaning on the door jamb. Mrs McNab would talk and my mother would regularly interject "Uhuh."

My father, sitting by the fire, behind the door, surrounded by his children, would repeat it softly every time my mother said it. There was no wireless and no television. Sometimes there was no light and never were there any pennies to spare.

But there was laughter as well as tears and an awareness of other people's lives.

No comments:

Post a Comment